[Essay] Masters of Spain: Goya and Picasso Essay

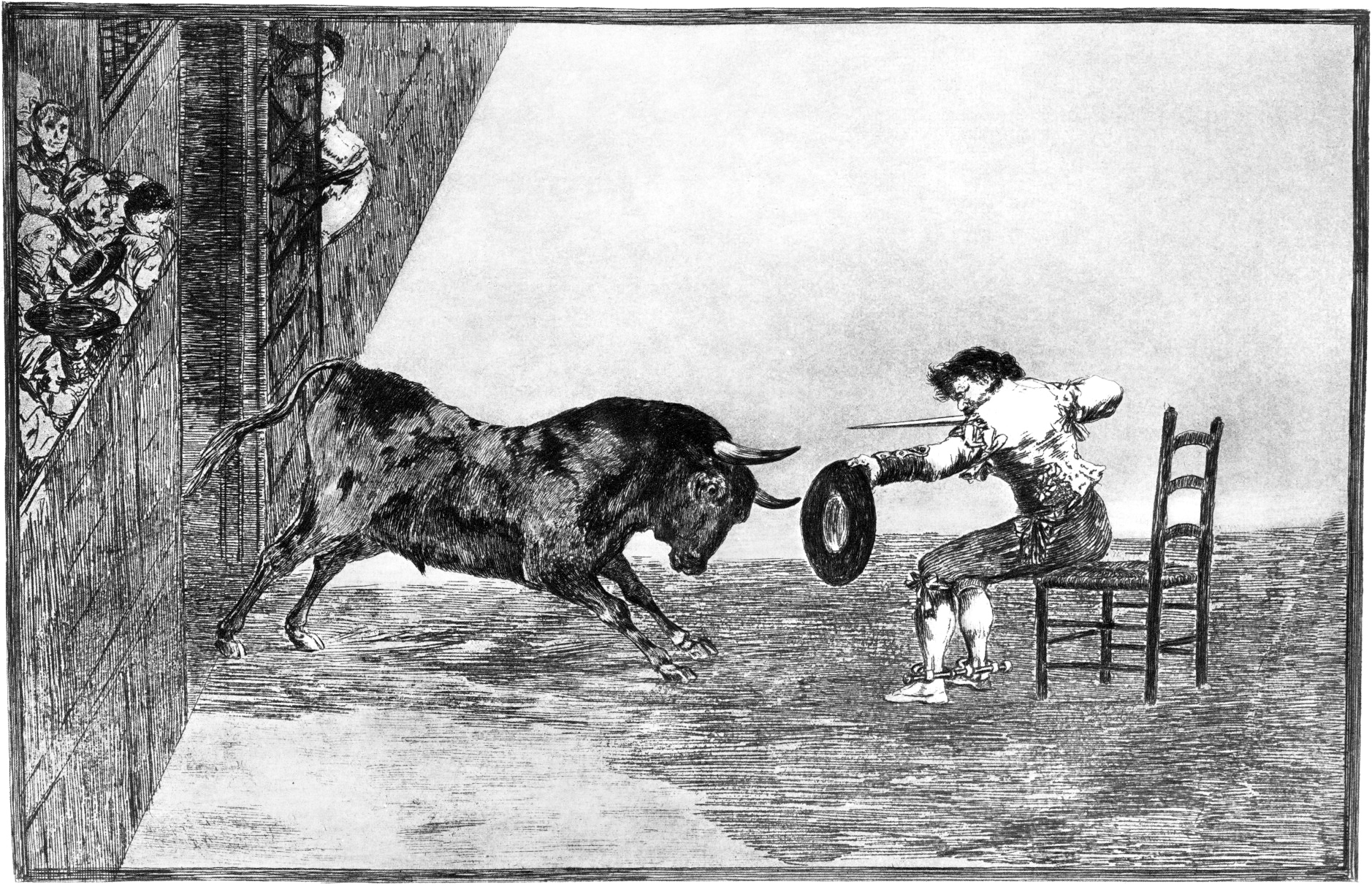

/Francisco Goya, Termeridad de martincho en la plaza de Zaragoza, 1815-16, Etching, Image courtesy The Art Company.

In keeping with our mission to offer incomparable world-class art experiences for the community, this exhibition brings to Polk County a rare showcase of work by two of the greatest Spanish painters of all time. Both considered masters in their respective eras, Goya was the most famous Spanish painter of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and Picasso of the twentieth. Masters of Spain: Goya and Picasso, then, presents the two artists who defined Spanish-made art for nearly two hundred years side by side and in important visual dialogue with one another.

With instantly recognizable styles, subject matters and techniques that inspire artists to this day, Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) form an interesting pair. While Goya made his name in Spain proper, initially as the First Court Painter of King Charles IV, Picasso became famous abroad in France — and Paris, in particular. Both lived very long lives — 82 and 91 years respectively — allowing them to see their worlds transform around them during rapidly changing eras in Europe, ones steeped in innovation, conflict, and cultural brilliance. And to be certain, Goya’s legacy as the outgoing Spanish art star was felt strongly by Picasso as he strove to take up that mantle.

THE TAUROMAQUIA SERIES

In Goya’s Tauromaquia (Bullfighting) series, the complete 33-print suite of which is exhibited here, Goya explores Spanish bullfighting from its earliest origins in ancient Iberian times to the arena sport we most envision today and which reached its hey-day in the nineteenth century during Goya’s lifetime. Produced late in his life and undated, but published in 1816, the prints in the suite show not only Goya’s dedication to focused subjects — as seen especially in his expansive Disasters of War series of 1810-20 (clocking in at 82 prints in total) — but also his inimitable technique as a draftsman, here using etching, aquatint, drypoint, and burin.

Goya designs his compositions to highlight the essential details of the bullring, often cleverly using negative space and a careful mix of light and shadow to characterize the movement and theatricality of the fight. Whether positioning the viewer at a high vantage point over the scene (as if perhaps in the stands) or in the arena alongside the matadors, Goya does not glamorize the bullfight. Just as in life, there are victories and there are tragedies here, Goya seems to say. As he does in all of his emblematically Romantic work — that is, non-hagiographic art that acknowledges the dramatic highs and lows of history — Goya tries always to convey a more truthful reality to his viewers.

THE PENINSULAR WAR

Goya turns to the quintessentially Spanish subject of the bullfight following the Peninsular War (1807-14) and the overlapping Spanish War of Independence (1808-14), a period in which the Spanish spirit was profoundly demoralized. This was an era of great social and cultural upheaval in Spain, during which Spain initially allied with France to protect its claim on the Iberian Peninsula from the United Kingdom and Portugal — only to see France turn on Spain in 1808, as an avaricious Napole0n sought to expand his empire. From 1808 to 1814, the French occupied Spain, a crushing six-year span under siege from the north (Goya himself referred to the period as “el desmembramiento d’España — the dismemberment of Spain”).

By 1814, two years before the Tauromaquia suite was published, Spain was fighting for its life, culture, and heritage under French occupation. As a result, Spain allied with virtually every other European country, including its former enemies (the United Kingdom, Portugal, German states), to defeat Napoleon’s forces in 1814. Despite successfully expelling Napoleon’s forces, Spain suffered socially, economically, and politically in the years following its fight for independence, with uprisings and civil unrest continuing through the middle of the 19th century. Before and after the Peninsular War, Goya found great success with royal commissions, but the intervening years of national instability during the French occupation left their financial toll on him as they did the country as a whole.

SPANISH PRIDE & THE TAUROMAQUIA SUITE

The depression of the Spanish spirit after years of foreign occupation by the invading French during the Peninsular War seems to have deeply motivated Goya, inspiring him not only to recount the horrors of the war years in his Disasters of War series but also in his Tauromaquia suite to revive a crucial element of the collective Spanish psyche. After years of political and social tumult, he seeks in the Tauromaquia suite to find the core elements of what makes Spain “Spain” and what makes Spaniards “Spanish.” In both series, Goya chooses to forego the brilliant color of his painted work, preferring a more straightforward, unembellished truth in these prints via his carefully rendered use of shadow and shading.

PICASSO, THE MODERN MASTER

If Goya is the undisputed Spanish master of the nineteenth century, Picasso raises the stakes in the twentieth century, becoming not merely the most revered Spanish master of his day but arguably the most renowned artist of modern art history. Hoping to upturn the entire history of art that preceded his own time, Picasso pushed all boundaries, pursued multiple styles (often all at the same time), and delved deeply into all media. Whereas Goya’s Romantic truth falls on the side of candid realism, Picasso’s truth is one that lies in the power of modern art itself. As the mixed-media Picasso pieces presented in this exhibition aim to demonstrate, Picasso’s oeuvre (body of work) goes far beyond paintings with seemingly jumbled faces. With his work in ceramic in juxtaposition here with his works on paper and even with a pendant pair of late Picasso portraits imaginaires on corrugated cardboard, we gain an intimate glimpse at an unusual, lesser-seen side of Picasso. Looking at a painted plate with a simple and beautiful still-life or a Goya-like depiction of a Corrida (1953), placed beside a vase transformed into the head of a woman, one can discern how swiftly Picasso juggles media and manners (wildly child-like at certain moments and exquisitely detailed and meticulous in others).

THE ECLECTIC PICASSO

Trying to identify a through-line in Picasso’s career is a wonderfully futile task. While certain subjects and styles recur heavily, Picasso is never producing art in any singular manner. As a result, Picasso is almost like a performer in a repertory theatre company, able to juggle multiple artistic styles simultaneously. This accounts for both the great diversity identifiable in any one year — or even any one week — of Picasso’s creative production and the prodigious output of his nine decade career (it is estimated Picasso created more than 20,000 works in his lifetime).

Picasso remains best known to the general public today as a “cubist” painter, but in reality the cubist period occupies only a small blip in an astonishingly lengthy career. While evidence of his groundbreaking cubist explorations — looking at objects from multiple vantage points at the same time — can be seen in the majority of his work through to the end of his life and in many of the pieces in this exhibition, Picasso is never strictly a cubist. Indeed, whereas cubism centers on a limited color palette of earth tones and overlapping planes, Picasso’s post-World War I work carries his innovations of the cubist period into more expansive examinations of color, form, mixed media, and flattening of the picture plane. The ceramics in this exhibition, in particular, showcase Picasso’s clever use of three-dimensional objects as the unlikely picture planes upon which to paint what often seem like naively-painted figures.

PICASSO’S CERAMICS

During the summer of 1946, Picasso attended a craft exhibition in the town of Vallauris, France. There he met Georges and Suzanne Ramie, owners of Madoura Pottery. He worked briefly at their studio and quickly shaped three pieces. When Picasso returned to Vallauris in 1947, he brought with him a number of drawings that he intended to convert into ceramic designs. The staff of Madoura Pottery worked with Picasso that summer and intermittently during subsequent visits over the next 25 years. Picasso moved to Vallauris between 1948 and 1955, and ceramic production became his principal focus. Ever the anti-student, Picasso never learned the proper methods for throwing a pot on a wheel or overcoming the technical challenges of glazing and multiple firings. Instead, he modeled his works directly from a lump of clay, decorating plates, dishes, and vases with the subjects that had preoccupied him his whole career: bulls, bullfighting, his models, his mistresses, still lifes, owls, goats, and roosters. To Picasso, an artist who had begun using found objects like newspaper, cardboard, and wire in his work as early as 1912, ceramics were as high and fine an art form as any.

PICASSO IN SPAIN

Although Picasso cemented his status as the great young artist of Paris with his seminal masterwork Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), his Spanish heritage was never far from his mind. He returned to Spain frequently, discovering ancient Iberian art in 1906, developing the early roots of Cubism there a few years later, and, in 1937, producing what may be the most famous painting of the century, Guernica, which commemorated the devastating bombing of the Basque city during the Spanish Civil War. The mural-size painting, now in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, has since become a universal emblem of the pitiful consequences of war. Much as Goya’s love of the symbol of the bull drives Picasso’s own frequent re-visitation of the bull-minotaur theme, Goya’s Disasters of War series served as a key inspiration for Picasso in his empathetic look the brutality of humanity.

H. Alexander Rich, Ph.D.

Curator and Director of Galleries & Exhibitions

Assistant Professor of Art History

Art History Program Director

March 2018